Archive

Violence

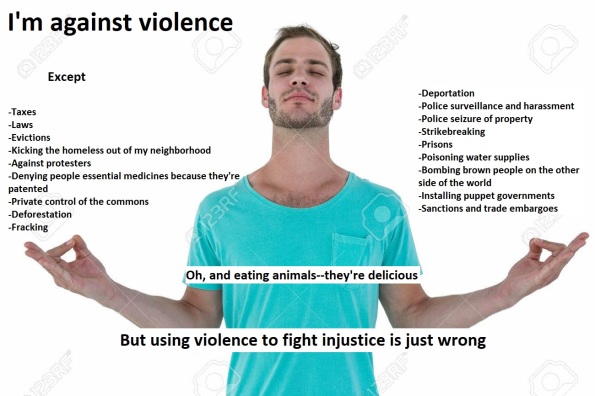

Several years ago, I wrote about the virtues of the Non-Aggression Principle, or NAP. I mistakenly wrote that anarchists (ie. most anarchists) believe in it. However, the more anarchist and revolutionary material I have read, the more I see the NAP as unnecessarily limiting.

Non-aggression means you should never initiate force against other people, and that force should only be used defensively. Inextricably linked is the right of property, which I discussed recently.

The NAP is a fine rule for interpersonal relationships and would be a reasonable way of organizing a small community. But when we live in a world where rich people pull the levers of the state and make decisions to evict people from their homes, steal their livelihoods, pass unfavorable laws and use the police to hold us down, fighting back should be considered self defense.

Similarly, white supremacists and fascists necessarily believe intimidation of and violence against vulnerable minority groups is legitimate. But many people who follow the NAP as an ironclad principle seem to believe only those who actually wield the weapons are legitimate targets. Many ancaps will tell you reasoned discussion with or about these people is the best or only way to defeat them, or otherwise tax evasion or secession. While all these options are ideal, they do not solve the pressing need to protect people from predators.

If someone is on the corner preaching hate, that person could gain a following, which could turn into a gang, attacking people it deems worthy of attack, or a political party, which could become a ruling party. Dangerous people will hide behind “freedom of speech” until they gain power, by which time it is too late to stop them. To be nipped in the bud, you could try reasoning with the person or satire, but if these things do not work, intimidation and the threat and application of discriminate violence should not be taken off the table. Why not make these people afraid to leave their houses?

This last question is particularly timely. Far-right, fascist, neo-Nazi movements are on the rise in North America and Europe. They are organized, motivated and gaining in popularity. They are using violence to take control of the streets. Ancaps make ignorant claims that anti-fascist (antifa) organizing and violence make antifa just as bad as the people they oppose. They actually take the side of the fascists and say antifa call everyone they disagree with fascists to legitimize violence against them. While of course that might happen on occasion, ancaps should know better than to believe everything they hear in the media as representative of all anti-fascists. Ancaps have no strategy for dealing with such people except to sit back, let them take power and then criticize them when they do.

Many ancaps falsely accuse anti-fascists of calling everyone else bigots and fascists in order to legitimize using violence against them. This claim is largely baseless. While there are undoubtedly some that do so, there is no reason to believe it is a normal practice among anti-fascists. Moreover, this wide generalization should be above any ancap who claims to oppose “collectivism”.

In August 2017 ancaps criticized antifa again for attacking fascists for marching and making speeches while some of the same people were attacking innocent people in the same town. They claimed it is fine to prevent people from committing violence but their preaching of hate and violence is all right until they act on it. That is not how it works. The incitement and the violence are very closely linked. You cannot have one without the other. As such, you do not get to select which counter-violence you like to condemn. It was all necessary to stop the threat. Letting them organize would have multiplied the violence. Learn to see the real threat. Stop holding the “freedom of speech” of fascists and bigots in such high esteem. Stop criticizing the people who are doing something about this serious problem.

The above situation about hate preaching could be likened to that of US soldiers during the Vietnam War who fragged (killed) their superior officers. One could argue the officers were merely advocating violence, not actually committing it themselves. But the killings were an act of resistance to an aggressive and tyrannical war machine, and probably played some role in ending the US’s prosecution of the war. How could it not be justifiable?

Did these people end the war, or did the Vietnamese and US troops who raised the cost of war too high to continue it?

I would take the utility of violent resistance one step further. If a group of owners and bosses is reducing salaries, cutting pensions, firing employees and attacking strikers for no other reason than to protect their pocketbooks, it is all very well to say “go and start your own business then” or “you should have saved your money”, but that does nothing for the newly impoverished. Can you explain why taking away someone’s source of income is not violence (even though security guards and police are there to protect legal owners) but smashing the windows of the decision makers is?

What if a board decides to poison a river people or animals rely on for their health? Is that not violence? And what if it is not clear who the precise decision makers were because the board does not make its meeting minutes public? Surely, attacking members of the board would be an act of self defense, whether to prevent them from doing it again or to prevent others from doing the same. If you do not agree with using overt violence against them, why not at least fight back some other way, say, by taking down their websites, hacking their emails and hacking their bank accounts?

A purist adherence to non-aggression would prevent someone made unemployed and homeless by the force of the political-economic system from, say, breaking into a supermarket and stealing food. Even though ancaps are well aware the system robs some people of everything they have, they have no solutions for those people besides charity. What if the sum of everything given to charity is insufficient to feed and clothe and house all the people in the streets? Ancaps would tell those people to wait for the generosity of others, because stealing food from a business is a violation of the NAP. Thus, to reiterate, while the NAP can work for small groups, it is not ideal under this system of plunder.

I understand the hypothesis violence against even worthy targets leads to the expansion of the police state. But the police state will take any excuse it can to expand, and in the absence of a reasonable excuse it will fabricate one. If we stand by and watch rather than fighting back, we have already lost. Many people, particularly ethnic, religious and gender minorities, are already subject to the kind of abuse you fear will be brought down on all of us. If we are trying to reduce the amount of violence and repression, we will need to fight back against oppressors. We can start by recongizing and supporting the struggle of marginalized and brutalized people and stop criticizing their methods. That is what is meant by solidarity.

In a world where the people in power do not respect the NAP but those who do refuse to invoke it to fight back, it amounts to pacifism, and pacifism is a luxury. Ward Churchill, in Pacifism as Pathology, writes

If you feel a relative absence of pain, that is testimony only to your position of privilege within the Statist structure. Those who are on the receiving end, whether they are in Iraq, they are in Palestine, they are in Haiti, they are in American Indian reserves inside the United States, whether they are in the migrant stream or the inner city, those who are ‘othered’ and of color in particular but poor people more generally, know the difference between the painlessness of acquiescence on the one hand and the painfulness of maintaining the existing order on the other.

And at what point is it legitimate to start fighting back? Only when we are certain they are killing innocent people? Secrecy makes such knowledge impossible. Look at the Holocaust. Most people did not know it was taking place until it was over. Derrick Jensen, also in Pacifism as Pathology, puts it thus:

One of the smartest things the nazis did was make it so that at every step of the way it was in the Jews’ rational best interest to not resist. Many Jews had the hope–and this hope was cultivated by the nazis–that if they played along, followed the rules laid down by those in power, that their lives would get no worse, that they would not be murdered. Would you rather get an ID card, or would you rather resist and possibly get killed? Would you rather go to a ghetto (reserve, reservation, whatever) or would you rather resist and possibly get killed? Would you rather get on a cattle car, or would you rather resist and possibly get killed? Would you rather get in the showers, or would you rather resist and possibly get killed? But I’ll tell you something important: the Jews who participated in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, including those who went on what they thought were suicide missions, had a higher rate of survival than those who went along. Never forget that.

…

They tell us that if you use violence against exploiters, you become like they are. This cliche is, once again, absurd, with no relation to the real world. It is based on the flawed notion that all violence is the same. It is obscene to suggest that a woman who kills a man attempting to rape her becomes like a rapist. It is obscene to suggest that by fighting back Tecumseh became like those who were stealing his people’s land. It is obscene to suggest that the Jews at who fought back against their exterminators at Auschwitz/Birkenau, Treblinka, and Sobibor became like the Nazis. It is obscene to suggest that a tiger who kills a human at a zoo becomes like one of her captors.

…

All of this closed-mindedness–this intolerance for any tactics save their own (one pacifist in his review of Endgame wrote “Give me Gandhi or give me death!”)–is harmful in many ways. First, it decreases the possibility of effective synergy between various forms of resistance. Second, it creates the illusion that we really are accomplishing something while the world continues to be destroyed. Third, it wastes valuable time that we do not have. Fourth, it positively helps those in power.

We already know the state and its patrons are killing people. The time to resist is now, before they can grow too large to challenge.

Peter Gelderloos in How Non-Violence Protects the State (which I strongly recommend) also puts forward the idea of effective synergy among forms of resistance, a diversity of tactics, as he calls it. No thoughtful revolutionary thinks in terms of purely violent resistance, as it is likely to lead to dictatorship or chaos. But if violence is used strategically and combined with educating the public (including through satire), counter-economics, boycotting corporations and taxes, strikes, the takeover of the means of production, building decision-making and mutual-aid structures, community and personal autonomy and secession, there is the chance of meaningful change and even revolution.

We are the true anarchists

My fellow anarchists, please stop this yellow-red, ancap-ancom, East-West-rap feud nonsense. You have nothing to lose but your chains.

Many anarcho-capitalists (and voluntaryists) and anarcho-communists (and mutualists) claim to be the only true anarchists. This claim is unhelpful, divisive and unfair. They claim the ideas of the other side would lead to a mere rearranging of capitalist property relations or rehashing old, failed communist policy. These claims are unlikely to be true, as, whether you can admit it or not, all anarchist theories are revolutionary. If you do not see that, it is unlikely you have spent much time trying to understand them.

This feuding is, in fact, typical of people who do not expect to succeed in their missions. The main political parties in any country work together, at least on some issues; the weakest are constantly bickering among themselves. It is possible governments place agents provocateurs among anarchists and other minorities to keep them divided. I do not know how to tell such a person online. Suffice to say, it is easy to make a guy feel he is right and you (and your whole team) are wrong: just dismiss his argument without appearing to consider it. We can resist these divide-and-conquer tactics by committing to unity of principle and purpose while encouraging diversity of opinion. But it tends not to work that way in practice.

Stupid anarcho-communists still don’t understand that we have to have property rights to have a free society. Damn anarcho-capitalists want to maintain hierarchies and classes by allowing property and bosses. They are not even anarchists! Anarchists are what I say they are. Well, are you against rulers? Then you are all anarchists. The debate rages, while the stateless society is still a glint in the revolutionary’s eye. Is there nothing more laudable on which we could be spending our time? Many anarchists spend hours a day arguing over the minutiae of what a stateless society should look like. They get angry and fall into disunity over questions that do not matter at present. The common goal is the removal of the state. The target is clear. It does not matter how many feathers are on our arrows. Work together. It is not as hard as you are making it.

I have a problem with anarcho-capitalists who claim a kind of absolute right to property. What if some people do not have anywhere to stay and want to squat on land you have claimed? What if they want to drink from a river or a part of a river you call your own? Anarcho-communists would say that is aggression. They also point out there is possession, distinct from property, which means you can hold on to something. But simply because you had more money or got there first is not a good reason that you have permanent and complete power over it.

Green anarchists would also point out though homesteading may not mean stealing from another human, it may destroy the environment and steal from other living things. Build homes, but do not shoot anyone who steps on your lawn. Build farms and factories, but not so big they flatten the landscape. At an extreme, property is illegitimate to someone who believes aggression is immoral.

My problem with anarcho-communists is the likelihood that a society without any ownership at all leads inevitably to the tragedy of the commons. Not all property is legitimate, nor does it need to be in the hands of individuals when it could be held by communities; but it seems necessary to me that someone consider it their property in order to take care of it. Property is useful because in a world of scarcity and anonymity, all resources are contestable and many of them will be contested. We can assign property to the person and people with the best link to the resource, thus making conflicts far easier to resolve. See chapter 3 of my book for further discussion of property in a stateless society.

So I disagree with you but I disagree with everyone on something. That does not mean I am not the right kind of anarchist and should be insulted and cast aside. It means I have something different to contribute.

Until you convince another few million people, your ideal society will be little more than a dream. You might need to work with others–especially those whose ideals are actually pretty similar to yours–to achieve it.

The alternative to the state, part 6: breaking free

“Once one concedes that a single world government is not necessary, then where does one logically stop at the permissibility of separate states? If Canada and the United States can be separate nations without being denounced as in a state of impermissible ‘anarchy’, why may not the South secede from the United States? New York State from the Union? New York City from the state? Why may not Manhattan secede? Each neighbourhood? Each block? Each house? Each person?” – Murray Rothbard

The worst thing the British ever did for India was to unite it. India is a vast country of a billion people with nothing in common. As many as a million people died and 12m were displaced when India was partitioned. Today, an insurgency in the east of the country started and continues because of a central government stealing their land in the name of “development” that the people are not interested in, and 100,000 farmers have committed suicide. India has gone to war with Pakistan several times and approached nuclear war over a border clash. None of these things would have happened if India had followed Gandhi’s vision.

“The ideally non-violent state will be an ordered anarchy,” said Gandhi. He believed India should comprise independent enclaves that were not subject to violence by powerful governments. His idea of swaraj, which means self-rule, was how to avoid domination by foreign rulers. It meant continuous effort to defend against subjugation. “In such a state” of swaraj, said Gandhi, “everyone is his own ruler. He rules himself in such a manner that he is never a hindrance to his neighbour”. Swaraj is not just about throwing off shackles but creating new systems that enable individual and collective development. Unfortunately, the forces of power prevailed, and India became ruled by rapacious Indians only marginally better than foreigners.

“The ideally non-violent state will be an ordered anarchy,” said Gandhi. He believed India should comprise independent enclaves that were not subject to violence by powerful governments. His idea of swaraj, which means self-rule, was how to avoid domination by foreign rulers. It meant continuous effort to defend against subjugation. “In such a state” of swaraj, said Gandhi, “everyone is his own ruler. He rules himself in such a manner that he is never a hindrance to his neighbour”. Swaraj is not just about throwing off shackles but creating new systems that enable individual and collective development. Unfortunately, the forces of power prevailed, and India became ruled by rapacious Indians only marginally better than foreigners.

Many statists believe we need national organisations and associations. But I do not understand why. Most decisions could easily be taken on a personal level, and the ones requiring collective action could come on the community level. As I have made clear on this blog, voluntary collective action is realistic and preferable to coercion. Democracy cannot be said to offer true freedom to the individual without freedom from the government’s every edict. In Democracy: the God that Failed (p81), Hans-Hermann Hoppe explains “[w]ithout the right to secession, a democratic government is, economically speaking, a compulsory territorial monopolist of protection and ultimate decision making (jurisdiction) and is in this respect indistinguishable from princely government.”

Let us go further into justification for secession. Here is Scott Boykin on the subject.

“Modern political thought has produced three main types of argument for the state’s legitimacy. One, found in Kant, grounds the state’s authority on the purported rightness of its institutions and aims.” By whose judgement? If the individual is the judge of what is right and wrong, the individual who deems the state’s institutions and aims wrong has the right to secede; at least, the individual who practices non-aggression.

“Another, found in Locke, holds that consent, whether explicit or tacit, is the source of the state’s authority. A right of secession challenges this-position in maintaining that consent may be legitimately withdrawn in favor of an alternative political arrangement.” If democracy is based on the consent of the governed, does that mean one can withdraw one’s consent?

“The third, found in Hume, bases the state’s authority on its usefulness in producing order, which facilitates the individual’s pursuit of self-chosen ends.” The modern state, in a variety of legal ways, destroys order and limits the individual’s choices. Therefore, you have the right to secede.

You, an individual, and your family and friends, can opt out of a system based on violence. No, I do not mean you can leave and go somewhere else. All countries, by definition, have governments, and government, by definition, is force. I mean you have the right to end a relationship with those who threaten you with violence.

Community secession

To start, however, I recommend secession on a community level. The only reason I advocate community secession is that no political entity will recognise an individual who secedes until the right to do so is itself recognised, which might not be for a long time. It may be just as true that national governments will not recognise local secession either; the history of secessionist movements is, after all, the history of central states’ making war on separatists.

As I have written elsewhere, anarchy exists and has existed in numerous places throughout history. It often arises during or after a war, revolution or other crisis. Those things may be coming to democratic countries, as they have in Greece and to a lesser extent the US with the Occupy movement. Think how hard it is for the people to change everything from how bad it is now. As a result, many are realising they can make a better society on a local level. They are leaving the state and the banks and the big corporations behind and making a new start.

Thus, we can start sovereign communities. The sovereign community is not subject to the authority of any state besides a local one its members have all willingly signed on to. Naturally, the “community” could be as big as it wants, provided positive consent is granted. It would enable everyone who wants to escape the state to do so, while not dismantling it for those who still want to live under a state system.

I propose entire communities separate, one by one, from the state. They might use legal means and go through the courts, as law is how things get done in a statist society. The sovereign community would not be cut off from all other communities; there is no doubt people would still visit each other. They would just not pay taxes or consume government services. They would make their own rules.

How to break away

Breaking free of the state could be undertaken bit by bit, as in these communities.

–The town council of Sedgwick, Maine, unanimously passed a law exempting the people of the town from all external laws related to food. Federal laws prohibit the growing and selling of certain foods; these people do not care. They have declared food sovereignty.

–Some places are moving away from fiat currency imposed by central banks. Greece’s current situation of lawlessness is leading many to adopt a cashless economy. Barter exchange has become the norm for many Greeks.

–That said, the Greeks may have been forced to act this way with the collapse of the Greek economy. Other communities are taking similar measures without being forced by circumstance to do so. Pittsboro, North Carolina, issues its own currency. It already had the US’s largest biodiesel cooperative, a food cooperative and a farmers’ market. Now it has taken a further step toward self sufficiency. According to Lyle Estill, a community leader, the currency has experienced no inflation. And Pittsboro is not the only one. Cities and towns around the US are rejecting Federal Reserve notes for circulation.

–Other communities are passing laws that refuse to recognise federal laws regarding corporations, such as corporate personhood. More than 100 municipalities in the US have passed ordinances prohibiting multinational corporations from dumping or spraying toxic chemicals, building factory farms, mining, fracking and extracting water.

–The Free State Project aims to make New Hampshire the first state to secede (successfully) from the US. The idea is for libertarians to congregate in order to have the biggest impact. (Not all anarchists agree on this strategy, incidentally.) New Hampshire is not the only state hoping to secede, with independence movements in California, Texas, Wyoming, and presumably other states I am unaware of.

–Keene, New Hampshire, has become a kind of centre for anarchist activism, encouraging the liberty-minded to flock there. It has not seceded from the US but might do in the future. Its people engage in all kinds of agorism, mutual aid, outreach education and civil disobedience. Learn more here and here.

–Like Keene, anarchists and socialists gather in Exarcheia, a part of Athens, Greece. It houses many organic food stores, fair trade shops, anti-authoritarian and anti-fascist activism.

–Like Keene, anarchists and socialists gather in Exarcheia, a part of Athens, Greece. It houses many organic food stores, fair trade shops, anti-authoritarian and anti-fascist activism.

Such piecemeal changes can be steps toward freedom and independence for one’s community, but they could just be a declaration of sovereignty over one particular thing members of the community do not want controlled by someone else. Alternatively, people could break away entirely from the state in one fell swoop. Has anybody done that?

–The Lakota nation, an American indigenous group, seceded entirely from the United States of America. It canceled all treaties it held with the state and its members renounced their citizenship. They hope to reverse the enormous harm 200 years of incorporation into the US has caused.

–Seasteading is an option that becomes more viable every year. Seasteading means building new homes on barges, ferries, refitted oil platforms or islands out in the ocean. Most have been unsuccessful, succumbing to natural disasters or lack of support. That is no reason to write off the whole idea. The real challenges are in construction and, as with all sovereign communities, escaping the violence of the state. Seasteading might not only mean building homes, but also resorts, casinos, aquaculture, deep-sea marinas and even universal data libraries free from copyright laws.

—Freetown Christiania, is an enclave of Copenhagen with just under 1000 residents. It is a self-governing and self-sustaining community which, though officially part of Denmark, is de facto largely independent. It began in 1971 and has become a kind of sanctuary for outcasts such as single mothers and drug addicts. The people make rules by consensus and have banned hard drugs, though marijuana and hashish have been sold openly.

—Freetown Christiania, is an enclave of Copenhagen with just under 1000 residents. It is a self-governing and self-sustaining community which, though officially part of Denmark, is de facto largely independent. It began in 1971 and has become a kind of sanctuary for outcasts such as single mothers and drug addicts. The people make rules by consensus and have banned hard drugs, though marijuana and hashish have been sold openly.

–As mentioned in previous posts, the Yubia Permanent Autonomous Zone in California is an example of a community that has broken away from the state and established communities based on the non-aggression principle. “The most important thing to understand about Yubia,” says its website, “is that it is not only a place — it is a way of being.”

–These things could happen on a much wider scale. One goal of anarchism is to reduce our vulnerability to repression by the state. We can develop alternative economic and security organisations and decision making. People have already started decentralising the internet, making it harder to implement a kill switch. Hackers, who were once mischievous teenagers, have grown up and have launched satellites to enable a free internet outside of the state’s reach.

–Similarly, in an economy based on a single currency that is regularly debased by a central bank, a new form of online currency known as bitcoin has emerged. It has the chance to revolutionise global finance. One article explains its significance: “There’s decent incentive for small businesses to use it—it’s free to use, and there aren’t any transaction fees. At the moment you can buy the services of a web designer, indie PC games, homemade jewelry, guns, and, increasingly, illegal drugs. If the internet is the Wild West, BitCoin is its wampum.”

–Or we could eliminate money. Setting up a resource-based economy based on the vision of the Venus Project and Zeitgeist holds wide appeal. Some people call their ideas idealistic. Who knows until they try? For those who are interested in building such a society, let them do it. People will join if it shows signs of success. Set a time and a place, get together and make it happen.

–Though difficult without the support of those around, breaking free does not have to take place at a community level. Business and professional associations might decide to stop following pointless laws and paying taxes, while nonetheless continuing to act responsibly. Schools can ignore federal and state laws regarding curriculum or the hiring and firing of teachers, instead making those decisions in concert with parents and perhaps students.

Unfortunately, these things are only possible when enough people, let’s say a critical mass, agree and are willing to fight for these rights against the state they are compelled to obey. The biggest danger inherent in secession is the same one sovereign communities have had throughout history: the state does not give up control over anyone easily. But people are showing more and more that they are fed up of statism, and are doing something about it. Find more about breaking free at www.secession.net.

The alternative to the state, part 5: contract-based communities

“The future social organization should be carried out from the bottom up, by the free association or federation of workers, starting with the associations, then going on to the communes, the regions, the nations, and, finally, culminating in a great international and universal federation. It is only then that the true, life-giving social order of liberty and general welfare will come into being, a social order which, far from restricting, will affirm and reconcile the interests of individuals and of society.” – Mikhail Bakunin

The movie Bowling for Columbine showed a headline about a town in the US requiring everyone to own a gun. Naturally, most people in the theatre with me shook their heads. What a bunch of ignorant townspeople, right? But if you are in a place where you know everyone has a gun, how likely are you to break into someone’s house? Wouldn’t be a very sensible idea, would it? But even if you think it is a stupid idea, is it right for you to impose your beliefs on others?

I don’t know why it needed to be a government decision, but at least it was local, which makes it easy enough to move to the next town if you don’t like it—far more reasonable than expecting someone to move to another country or go live in the woods. In a stateless society, no one would be expected to move, because the possession or non-possession of firearms would have been a stipulation of the rules one would have already agreed to to be permitted to live in the community in the first place.

Now, in every democratic country, we have a race, a fight—always of image over substance—to see who will take the reins of power, so that the winner can impose his or her beliefs on the entire population by force. Would it not make more sense to have smaller groups in which people could live by the values they want? If abortion is murder, disallow it in your community; but why should millions of people who disagree with you be forced to follow your values? The option—the right—should exist to secede. Hans-Hermann Hoppe, in Democracy: the God that Failed, points out that “[s]ecession solves this problem, by letting smaller territories each have their own admission standards and determine independently with whom they will associate on their own territory and with whom they prefer to cooperate from a distance.” (p117)

In my last post, I suggest a variety of ways of using privately-produced law, such as arbitration, dispute-resolution organisations and insurance, to get the benefits of ideal state services without being subject to the wayward decisions of the elite. This post goes into detail on another, related idea of anarchists: the community based on a contract. This and the next post propose seceding from the state and building stateless, or sovereign, communities.

The sovereign community

When moving somewhere new, people are usually subject to certain by-laws passed down by the municipality, if such a level of government exists. Such laws might include not letting one’s grass grow too long or driving under 30kph in a school zone. In general, the lower down the level of government, the fewer people it represents, the more accountable it is. A government that presides over only a few thousand people, in fact, is barely a government. Unlike any other government, it would have little or no bureaucracy, few powerful lobbies and people would not need to rally en masse to make changes. A group of a few hundred people who make decisions on consensus is not a government at all, as there is no one imposing decisions on others.

The ideal unit of human organisation is not the nation or the race but the community. Dunbar’s number, the number of individuals the average human can maintain a stable relationship with, is between about 100 and 200, most likely because we evolved in communities of this size. In a community, people grow up around each other and share a culture. They know and learn from and trust each other. True communities make only minor distinctions between family and friends. Their members will defend each other and the community. Rules (or laws) are best made on the community level, because it is much easier to come to a consensus and ensure that the rules represent the wishes of everyone. Rule enforcement, too, would be far easier, because the enforcers would know the offenders. Shaming, ostracism and reconciliation are all much easier. And we do not need to get rid of professional enforcers and prisons for the truly recidivist criminals; we just would not pay unrepresentative and uncaring institutions to do it for us.

The exemplary sovereign community would counter the objection that statists have that anarchy can only mean killing each other wantonly. People who believe in this nightmare scenario not only do not read anarchist ideas on preventing that possibility; they disregard the enormous differences between the modern world and the stateless world of old.

-First, we are used to peace. Many hunter-gatherer societies are used to war. We are accustomed to diversity of culture, language, skin colour, ideas and ways of living. We no longer react toward people we have never seen before as members of other tribes who are likely hostile. We are used to peaceful interactions with all the thousands of anonymous people we meet over our lifetimes and get into intractable conflicts with maybe twenty of them. People who like peace will defend and build on it, just like people who appreciate their freedom will not give it up easily.

–Even in the past century we have become more peaceful. The decades leading up to World War One were marked by militarism in Europe. War was seen as salutary for a nation and a man. This feeling is now accepted far less widely. One can see evidence for this claim in the statistics alone: people are killing each other less now (relative to population) than any time in history. See Steven Pinker’s the Better Angels of Our Nature for statistics on and possible reasons for this development.

-Second, we can communicate with those members of other tribes in town hall gatherings, dispute-resolution organisations, or just over the phone in ways that even one hundred years ago was impossible. World War One was caused in part by poor communication among the warmakers. Unsure of each other’s intentions and lacking the easy long distance calling we take for granted, part of the march to war was, in fact, a blind stumble of guesses. We no longer suffer from the same lack of communication. Equally importantly, stateless societies would not have vast war machines at their disposal.

-Third, where most people see the inevitability of war, a better understanding of the causes of war reveals that states have, for hundreds if not thousands of years, nearly always been the initiators of war and the causes of terrorism. They make war to enlarge the power and wealth of the people on top. Through taxation and debt, they force their subjects to pay for it. Without the apparatus of legal plunder and the build up of militaries, war is far less likely.

-Finally, we have all the ideas necessary for peaceful and prosperous living, from ideas of stateless, democratic decision making to how to take care of each other through mutual aid.

I conceive of “community” in very broad terms. It could mean cities or something even larger, if they can somehow be managed, as well as towns; cooperatives of farmers or workers; or whatever other associations they want to put together. Individual communities’ making their own rules would mean anyone’s kind of anarchism can be attempted. You could try a propertyless commune or a Galt’s Gulch (let’s hope the capitalists and the communists don’t engage in a Cold War); whatever you think makes the most sense.

I use the word “rules” to differentiate what I am talking about from “law”. “Law” has a number of definitions but this blog goes by that of law as an imposition by uncaring elites on a populace, which is what most laws are. “Rules” here mean the things people have decided to follow, not just to make others follow. They are what people agree to when going to a new place and can be changed when they no longer serve the common good.

Some sovereign communities will have leaders of one thing or another, as do most or all communities. Leaders are great, but it is hard to lead hundreds of thousands of people without an urgent, common cause (which is why a sense of urgency and a flat hierarchy are important for large corporations to stay ahead of the competition). But leading on a smaller level is not a problem. Small groups are more flexible and can act like teams more easily than big ones.

Sample rules

If a community decides on a code of rules, it can institutionalise them by having those who want to live there sign a contract. The contract would say that the people living there would adhere to those rules if they wish to remain there. Some stipulations in the contract might read

–adhere to the non-aggression principle. It is possible to build a community entirely on this premise, with very few other rules. Freedom would be maximised, though there would be other consequences as well.

–join the mutual aid network, or certain aspects of the mutual aid network, such as neighbourhood watch, health insurance, pensions for old people, and so on.

–no private property. People who believe property is theft would probably want that in writing.

–no violence whatsoever. This one is for pacifist communities. I would not want to take away someone’s right to defend him or herself, but pacifists have a different point of view, and if they want to organise on that basis, they should be free to do so. (The problem is, of course, the danger from outsiders; living high in the mountains may eliminate this risk.)

–immigration rules. As good as immigration can be for an economy and for opening minds, for one reason or another, it is possible that a community would not want too many newcomers. Perhaps it would put a strain on the local environment. Perhaps they just do not like Paraguayans. I do not like racism, but I do not force others to accept my beliefs. Let immigrants go where they are welcome, where they can improve their lives and the lives of those around them.

–the minimum drinking or drug-taking age, and which drugs are prohibited.

–no parental abuse or neglect of children, or else the community intervenes and adopts them until the parent is rehabilitated.

–no Walmart. If communities want to protect local business and even foster infant industries, they can erect barriers to trade as selective as they like. No to big box stores’ setting up in this neighbourhood (or even no buying from such stores and bringing it home). Nowadays, we have the ability to trade with millions of people around the world. A community that makes its own rules does not need to be hampered by one-size-fits-all laws, tariffs and sanctions over whole nations written for minority interest groups.

—Communities and individuals would be able to decide with whom, anywhere in the world, they would trade. Hoppe again: “Consider a single household as the conceivably smallest secessionist unit. By engaging in unrestricted free trade, even the smallest territory can be fully integrated into the world market and partake of every advantage of the division of labor, and its owners may become the wealthiest people on earth.” (p115) Secession promotes economic integration to the extent independent units want it.

—Sovereign communities would likely form confederations with others, as was the case in pre-British-ruled Ireland, with no violence involved in leaving the group. They may prefer to trade with others of similar values. This principle is similar to the idea of buying fair trade, supporting small businesses over big or boycotting companies that abuse their workers.

–how to make decisions, and when not to. Not all decisions need to be made collectively. A man is free to the extent he does not have to follow decisions he disagrees with. But for those decisions that are made collectively, such as building a road or a school, the rules should specify a decision-making mechanism. The process most respecting of the individual is consensus. Consensus is, of course, rejected as a way of making decisions on the national level, but that is why it is preferable to do it on a lower level, where important things like new rules and punishments can be discussed by the people they will affect. The higher the level, the less representative decision making is and the easier it is for a majority to trample on a minority.

—If the community is too big for consensus, let the decision-making apparatus split and different people can choose which to join without moving. “Community” does not have to be an exclusive territory. As long as they agree not to impose their policies on others, they can live next to each other in harmony. Given what we know about polycentric law, such an arrangement is possible.

–rules for arbitration. My last post propounded a free market in dispute-resolution, arbitration and enforcement. But it is possible that a single community will have a single organisation in charge of arbitrating disputes among members. It may have an authority figure charged with ensuring decisions are enforced. The village policeman is often a friendly, respectable, trusted, admired member of society. It is not necessary to do away with him just because we do not like the FBI.

–penalties for non-compliance. These might start with simply talking to the violator for breaking smaller rules once or twice. Next could be public reprimand—singling out the person for criticism at a community meeting, and asking him or her how he or she will address the problem. A larger offense might require monetary compensation, perhaps working to pay off one’s debt to the victim. As a major punishment for something the community considers very offensive, probably after one or more chances to reform, the community could kick out the offender (or put it to a vote). If the offender is irretrievably violent and the people believe he or she requires deterring or punishing, they can lock him or her up. Of course, a society based on polycentric law would deal with these things equally well.

Whatever codes of ethics communities decide on, there is likely to be a great deal of similarity among them. Free communities will probably agree on some variation of the NAP, participating in a neighbourhood watch or sharing the costs of policing the streets, and so on. Some might be more entrepreneurial or socialist or fearfully protective than others, but most will probably still adhere to common norms. And when they share best practices, people get better ideas. Anything is possible when millions of people are free to decide.

The alternative to the state, part 2: agorism and counter-economics

Freedom, including the freedom to build and trade and innovate, is the natural state of humanity (as agorists will tell you: see the principles underpinning agorist theory here). If the state is meant to protect us from the bad people (it is not, but that is its perpetual justification), it follows that, if we are peaceful people who do good things for ourselves and others, we have the right to ignore the state. If one must ask permission, one is not free. Agorism is voluntary exchange without asking permission; taking one’s freedom back and using it to make people better off.

Freedom, including the freedom to build and trade and innovate, is the natural state of humanity (as agorists will tell you: see the principles underpinning agorist theory here). If the state is meant to protect us from the bad people (it is not, but that is its perpetual justification), it follows that, if we are peaceful people who do good things for ourselves and others, we have the right to ignore the state. If one must ask permission, one is not free. Agorism is voluntary exchange without asking permission; taking one’s freedom back and using it to make people better off.

Monopolies enable and encourage abuse. In Markets Not Capitalism (pp68-74), Charles W. Johnson explains that the state has a monopoly on huge swathes of the economy. It has a monopoly on security, and trillions of dollars’ worth of security apparatus to use as it likes. It owns land and natural resources, fabricating land titles, instituting complex land-use and construction codes, and the capture of others’ property by use of eminent domain. It controls the money supply, enriching bankers and criminalising alternative forms of currency that people could use to avoid inflation. It grants monopoly privilege to patent and copyright holders. It has a monopoly on the building of infrastructure, artificially lowering fees of transportation at the taxpayers’ expense, instead of turning it over to the private sector where it can save money and save lives (see here). It has a monopoly on regulation, which largely protects big business at the expense of small, creating new monopolies. Finally, it decides everything that crosses its borders, from the amount of goods and the fees for them to the movement of people. This blog has outlined the problems with most of these monopolies already. The question at hand is, how do we challenge them?

In the New Libertarian Manifesto, Samuel Edward Konkin glances at how libertarians have tried to end the state, from violence to collaboration to spreading the word. He concludes from their overall failure that the answer is to stop feeding the state, and outlines his vision for an agorist society, and the counter-economic method of getting there. Counter-establishment economics, or counter-economics, is simply peaceful action that the state forbids. It exposes the unnecessary and damaging role of the state in the enforcement of its monopolies.

Agorism has much to do with self sufficiency, shaking off dependence on the state and doing things for oneself and one’s community. In addition, while it means avoiding taxes, it is at least as much about starving the state of funds. If a person, or much better, community, opposes the state, he or it can set up businesses or co-ops that are unlicensed, unregistered, unregulated and illegal. They can provide goods and services cheaply and without needing to feed the beast.

Agorism means that one by one, people will stop supporting the state and start supporting each other instead. Agorists will be at the forefront of the building of a new society, and they provide an example for those who are interested. (More on the logic of agorism here.)

To make clear, drug barons are not agorists (as they do not believe the state is immoral) or counter-economists (as they use violence). It is unfortunate that it is necessary to use violence in drug markets, but that is a natural consequence of the criminalisation of something so many people want. But not all black markets are violent.

As the Movement of the Libertarian Left shows, counter-economists come in all shapes and sizes. They could be

As the Movement of the Libertarian Left shows, counter-economists come in all shapes and sizes. They could be

–Tax evaders (how-to);

–Smugglers (of humans looking for opportunities, drugs to people who need or want them, banned books, cigarettes subject to high taxes, and so on);

–Midwives whose positions have been eliminated by state health care systems;

–Doctors working without belonging to government-approved national medical associations;

–Gun owners who disobey firearm restrictions;

–Gamblers who gamble with friends instead of in registered casinos;

–Unregistered taxi drivers;

–Publishers and consumers of illicit art, literature and newspapers;

–Pirate radio operators (how-to);

–Farmers who grow and sell things the state prohibits, from hemp to raw milk;

–Cooks who make and sell food, perhaps to friends and neighbours, by mail order (like Stateless Sweets) or by the side of the road;

–Unlicensed contractors (how-to);

–Employers who pay under the table and employees who are paid under the table;

–People who pirate drugs or entertainment subject to intellectual property laws;

–People selling things at garage sales, roadside stands or on Craigslist;

–People who give sanctuary to others on the run, such as whistleblowers and runaway slaves;

–People feeding the homeless despite prohibitions on it;

–People using an alternative currency (such as bitcoin or others), and using encryption to transfer funds online (how-to);

–People engaging in reciprocal gift economies (like the Freecycle Network, Freegan, Food Not Bombs and the Really Really Free Market);

–And anyone competing with a government monopoly, like Lysander Spooner did. Looking at all these illegal (but victimless) activities, are you a counter-economist?

In the twilight years of the Soviet Union, just about everyone was. The state had proven itself utterly incapable of providing more than the bare minimum of all manner of goods that were, in fact, available on the black market: food, repairs, electronics, exit papers and favours from the powerful.

Occupiers, you are counter-economists. Occupy movements were entirely voluntary, working on consensus, anticapitalism, mutual aid, equality and solving their own problems. They established clinics, schools, libraries, kitchens and security teams. They showed everyone that we can have a voluntary society, that we can build a new society, based on compassion and helping each other, out of the shell of the old. It is called prefigurative politics. These values also inform the philosophy of the sovereign community, meaning new communities outside the reach of the state. Voluntary institutions show not only the morality of non-aggression, but also that we can solve the world’s problems without force.

Occupiers, you are counter-economists. Occupy movements were entirely voluntary, working on consensus, anticapitalism, mutual aid, equality and solving their own problems. They established clinics, schools, libraries, kitchens and security teams. They showed everyone that we can have a voluntary society, that we can build a new society, based on compassion and helping each other, out of the shell of the old. It is called prefigurative politics. These values also inform the philosophy of the sovereign community, meaning new communities outside the reach of the state. Voluntary institutions show not only the morality of non-aggression, but also that we can solve the world’s problems without force.

Learn more at agorism.info, www.humanadvancement.net, in the book Markets Not Capitalism and in the writings of Samuel Edward Konkin and the Movement of the Libertarian Left, available free online.

The alternative to the state, part 1: the sovereign individual

“The ultimate authority must always rest with the individual’s own reason and critical analysis.” – The Dalai Lama

Until we achieve freedom, we need to lay the groundwork. The state is best done away with by making it irrelevant. The groundwork is in the work we do, the planning and organising to separate from the state entirely, but it is also inside our minds.To become free, we must free ourselves. My term for those for whom only oneself can decide what is right is sovereign individuals.

To a sovereign individual, the supreme authority is the self. Only the individual can decide what is right for him or herself. Of course, he or she takes others into account. When driving, one takes care not to run into other cars. A sovereign individual lives the non-aggression principle because he or she believes in the silver rule: not doing to others what he or she would not want done to him or herself.

The sovereign individual believes in self ownership, meaning that the individual owns his or her actions and their consequences. A man owns the fruit of his labour and no one has the authority to dictate what any proportion of it can be used for. He enters into whatever voluntary associations and voluntary exchanges he likes, but would only be forced into them when he has no choice.

Sovereign individuals might also let others take responsibility for their own lives. Freedom and responsibility are two sides of the same coin. Helping each other is great, but when we try to force virtue, which might just be our opinions of what is right and wrong, others lose the chance to experience the freedom to figure those things out, and take no responsibility for the consequences.

Think about what we do with children: Not letting them play with knives and firecrackers, helmets for virtually every activity where they might get hurt, lying to them about the dangers of cigarettes and other drugs, hauling them to jail for starting food fights, or whatever universal rules for creating the ideal humans parents in a particular culture believe they have discovered. All these things are producing irresponsible and spoiled people who are easier to scare into giving up their freedom. We could just let them decide what they want to do on their own, giving them the freedom to get hurt and the responsibility to learn from it.

Most people think they know what is right for others, which I believe is why they participate in politics and want governments to control people. But do we know what is right? Do you like it when others tell you what to do, or argue with you about the right way to do it? If people want to work it out themselves, let them. Changing people is hopeless and unnecessary. People are affected more by others’ examples than by their words. If people decide that they want to be unplugged, take them with you. If not, leave them in the matrix where life is more comfortable.

Voting and other participation in politics is a way of trying to control others by force. Sovereign individuals avoid it. They also do not like taxing people because taxes are taken without asking and spent on repressing people. It may be possible to avoid paying taxes by various means: buying directly from manufacturers such as farmers, working under the table, and so on. It is easier when done with like-minded people, as they can use alternative currencies that are not subject to central bank manipulation, buy and sell from each other without government interference into markets or move toward a gift economy (all of which will be outlined in a future post). Suffice to say, supporting local businesses and farmers and boycotting businesses that receive favours from the government are worthwhile principles to live by.

Many people who consider themselves sovereign individuals are engaging in mutual aid and counter-economics. It can be hard to come by reliable reports because what they do is often illegal, and naturally they wish to remain under the radar.

But be careful about avoiding taxes, and about defending yourself against state aggression. IRS special agents are armed. They have been told that sovereign individuals are terrorists. And if you are known to owe back taxes, you cannot leave the US legally. Careful about living “off the grid”, too. People attempting to live outside the state’s reach are finding it impossible. An estimated 1% of Americans are attempting to escape the long arm of the state but are getting raided by thuggish police. Read some examples here. Peaceful people who want to be free are getting shut down by a state that looks to squeeze every drop of tax milk it can from the cattle it rules.

But it may still be worth doing. You may prefer to find somewhere with less zealous police and a government less focused on destroying individual freedom than the US. There is plenty of world out there where we can be free. A pirate’s life for me.

(For more on how to be an individual, read about my friend Dave.)

Principle versus expediency: how to save the world

Billions of poor people. Wars without end. Torture, disease, genocide, starving children. There are some major problems in the world. The question is, how do we do something about them? We have options. Some people say we need to take control of governments and force the changes rapidly. After all, people are dying now. This post will argue against hasty action.

We have become accustomed in the modern world to doing things fast. We want things now. This trend is reflected as much in activism as with everything else. How will we change everything? Revolution! Slow down. What kind of revolution? A revolution is a major event involving many people. It is impossible to predict the outcome of a revolution, and it is rarely (perhaps never) as the original revolutionaries envisaged. And the kind of revolution that takes place in the street inevitably means violence. Is an uprising, violent or non-violent, the best way to change the world? Let us continue with our options before deciding.

Another effect of wanting immediate results is a focus on elections. We need to field new candidates, ones that will do the right thing. Are there people like that? Look at the hopes of the Tea Party. After the Tea Party got some of its members elected on a small-government ticket, the newly elected voted for all the same big-government legislation as the other Congresspeople, and have even ended up with all the same campaign contributors. It turns out that a few new people could not make radical changes. One does not simply walk into Mordor.

Another effect of wanting immediate results is a focus on elections. We need to field new candidates, ones that will do the right thing. Are there people like that? Look at the hopes of the Tea Party. After the Tea Party got some of its members elected on a small-government ticket, the newly elected voted for all the same big-government legislation as the other Congresspeople, and have even ended up with all the same campaign contributors. It turns out that a few new people could not make radical changes. One does not simply walk into Mordor.

How about putting pressure on existing politicians? That can work. As little hope as I see in the political process, enough letters or enough protesters can force the hands of the elected. But what is the political solution? Remember, government is based on force. Every law passed is an order. If one does not follow the law, one risks arrest and all the violence that it results in. What we want to force on others may not be the best thing for them.

When we consider working through the system of force, we want to use the existing tools to do so. The state system has two basic tools at its disposal: taxation, which could be used to redistribute wealth, and law, which could be used to force people to act right. I am opposed to the idea of using the state on moral grounds. And as I will demonstrate, morality is not only an end; it is a means.

When we consider working through the system of force, we want to use the existing tools to do so. The state system has two basic tools at its disposal: taxation, which could be used to redistribute wealth, and law, which could be used to force people to act right. I am opposed to the idea of using the state on moral grounds. And as I will demonstrate, morality is not only an end; it is a means.

As I write in greater detail elsewhere, a simple but powerful moral rule is the non-aggression principle (NAP). The NAP states that the initiation of force or violence, including the credible threat of violence, against unwilling adults who have not initiated force themselves is immoral. Laws force entire populations. If we could opt out of laws, we would be free, but we cannot. Laws based on the NAP are moral but laws regarding what we wear, eat, drink and smoke, for example, are not, because those things do not harm others. There should be no law regarding victimless pursuits. Taxation means forcing populations to pay for whatever the government decides on. But not everyone in the population has aggressed against another, or is being taxed commensurately to his or her aggression.

Many anarchists believe in the NAP on philosophical grounds. They argue that, whatever is done with the money raised by taxation, whatever someone’s idea of virtue that informs the wording of a law, it is wrong to force peaceful people. More importantly, however, force is a terrible tool for solving problems, and tends to cause far greater ones.

Do taxation and regulation lead to a redistribution of wealth? Yes: from the lower classes to the rich. The basic reason for that is that the lower classes, including the middle classes, have no power over the state. The state has power over them; and in every society, it becomes a vehicle for transferring wealth from the people who are outside it to the powerful people who control it. We have had social welfare policies for decades and poverty still exists. But why are they still poor? Welfare policies actually entrench poverty by making people dependent on the state.

The best cure for poverty is, in fact, a free market. The free market just means free people trading with each other out of mutual benefit, without force. Tearing down the endless regulations and taxes that are designed to benefit the wealthy would give opportunities to everyone else to work as they like. How we could do that by using the state I do not know, because, again, laws benefit the powerful and the powerful control the state. It is impractical to use the state to solve society’s problems.

The best cure for poverty is, in fact, a free market. The free market just means free people trading with each other out of mutual benefit, without force. Tearing down the endless regulations and taxes that are designed to benefit the wealthy would give opportunities to everyone else to work as they like. How we could do that by using the state I do not know, because, again, laws benefit the powerful and the powerful control the state. It is impractical to use the state to solve society’s problems.

Could we use laws to force virtue? It depends what is virtuous. I agree with Penn Jillette on this one.

It’s amazing to me how many people think that voting to have the government give poor people money is compassion. Helping poor and suffering people is compassion. Voting for our government to use guns to give money to help poor and suffering people is immoral, self-righteous, bullying laziness.

People need to be fed, medicated, educated, clothed, and sheltered, and if we’re compassionate we’ll help them, but you get no moral credit for forcing other people to do what you think is right. There is great joy in helping people, but no joy in doing it at gunpoint.

The other question is, can the state actually be reconfigured to work for the greater good? Can it be sustainable if done by force and not spread throughout the population as common values? I am inclined to say no. If people can be led to believe in taking care of each other and taking care of the poor, they will do so voluntarily, as of course many do already. If they cannot, forcing them to do so could lead to a backlash. Look, for example, at the plight of some of the people in the democratic world who are most vulnerable: immigrants. Immigrants are people like everyone else, so surely they should all be permitted the same rights and freedoms. Letting immigrants into the US, Europe and the rest of the rich world meant giving them a chance to help themselves and their sending countries. But anti-immigrant forces first controlled the discourse and then the relevant areas of the state, and 400,000 people were deported from the US in 2011 alone. People escaping horrible conditions in Africa are left to drown in the Mediterranean. I take the sum of these and similar actions and indifference toward them to mean the people are not ready to be forced to take care of everyone else.

The state may be a lost cause, but we are not out of options yet. The problem is that the more viable solutions are long term. They require patience, not quick fixes. I think there are two basic things we could do. The first is to educate people—particularly ourselves—on the issues and how to solve them. We can keep the real issues foremost in the minds of people, so that we are the media and the teachers. That doesn’t just mean Facebook, of course. It could mean street protest and symbolic action to raise awareness. This process is neverending, so it is incumbent on concerned people to educate to the extent that others become the media and the teachers as well. The main downside to this option is that not everyone will be interested. But that just means they have better things to do, and I do not blame them for that.

But not everyone has to join us. The second thing is to organise with like-minded people. That means being leaders, working together, helping each other and doing things ourselves. The revolution does not have to be violent. Look at what Occupy did. They were entirely voluntary, working on consensus, anticapitalism, mutual aid, equality and solving their own problems. They showed everyone that we can have a voluntary society, that we can build a new society, based on compassion and helping each other, out of the shell of the old. It is called prefigurative politics. These values also inform the philosophy of the sovereign community, meaning new communities outside the reach of the state. Voluntary institutions show not only the morality of the NAP, but also that we can solve the world’s problems without force.

But not everyone has to join us. The second thing is to organise with like-minded people. That means being leaders, working together, helping each other and doing things ourselves. The revolution does not have to be violent. Look at what Occupy did. They were entirely voluntary, working on consensus, anticapitalism, mutual aid, equality and solving their own problems. They showed everyone that we can have a voluntary society, that we can build a new society, based on compassion and helping each other, out of the shell of the old. It is called prefigurative politics. These values also inform the philosophy of the sovereign community, meaning new communities outside the reach of the state. Voluntary institutions show not only the morality of the NAP, but also that we can solve the world’s problems without force.

The armed corporation

A common fear statists have of a free society is that a corporation, or some other large entity, would one day take up arms and attack and control people. In effect, this fear is the same as the fear of a government: that a small group will get together to take money and power away from a larger population. I agree that we must remain vigilant about such things, which is why free communities have many options for dealing with such a scenario.

As I explain in my post on human nature, humans have a sense of reciprocity: you help me and I will help you. The good guys, and good businesses that provide value to their customers, are the ones that succeed over time. That is why the image of the free market as the “law of the jungle” is erroneous. The law of the jungle is where the powerful come to dominate others, which is what a state enables. A free market means businesses would need to provide value, or they would not make money.

There are some psychopaths out there. We do not want to give psychopaths the means of violence, which is the main reason we should deny them access to the levers of the state. But they may also have access to large amounts of money through a corporation on the free market. They will lose from any customers who consider their actions illegitimate, but it is possible those customers will not know. That is why we have the media.

The huge variety of media in our society, from Democracy Now to Fox News to our friends and family, are one way to tackle organisations that act immorally, because consumers will withhold their dollars if they are deeply opposed to a business’s actions. Many consumers make choices based on their impressions of the companies they buy from. There have been a number of successful boycotts, which give more credence to the fact that businesses a) are beholden to the market and b) can be pressured by small numbers of ordinary people into changing for the better. Business groups such as the Better Business Bureau ensure that ethical businesses get certain benefits of belonging to clubs and the unethical ones get shunned.

All manner of organisation can use boycotts, along with public shaming of people involved, if their rules for ethical behaviour are broken. Shaming can actually be a powerful weapon, as we see when we see a man’s bad cheque on the side of a cash register. It can be used against those who violate the non-aggression principle, as has been suggested regarding police who use pepper spray on unarmed protesters. We need good reputations in life to be able to sign contracts, and we sign many of them in our lives. (Two people who have thought and spelled out the problem well are Stefan Molyneux on dispute resolution and David Friedman on private law.)

Since the people who own and run corporations would no longer have limited liability or other legal protections, the same rules apply to them as to corporations themselves, and anything I say about corporations must apply to the people who make them up. Through private law, people would be able to sue individuals working in the businesses who perform acts of aggression, rather than just suing the corporation. No corporate personhood, no bailouts and other transfers from taxpayers to corporate executives, no regulations preventing small businesses from entering the market: corporations would be far weaker without the state.

Since the people who own and run corporations would no longer have limited liability or other legal protections, the same rules apply to them as to corporations themselves, and anything I say about corporations must apply to the people who make them up. Through private law, people would be able to sue individuals working in the businesses who perform acts of aggression, rather than just suing the corporation. No corporate personhood, no bailouts and other transfers from taxpayers to corporate executives, no regulations preventing small businesses from entering the market: corporations would be far weaker without the state.

They would also have no legal mandate to make a profit, though it is more accurate to say that at the moment they must do what their shareholders want. As not all shareholders of all corporations are purely interested in making money, and others believe ethical behaviour is a way to make money, some of them have taken to shareholder activism, and have made positive changes in the corporations they own that way. Here we have yet another check on corporate power, and I see no reason to believe it would disappear without a government.

The idea that we should worry about private armies is misplaced. Whom does the national military serve? The elite control the state. The state and all its institutions serve the elite. A national military is the private army of the elite. It is paid for by the taxpayers, rather than the elite. In fact, the elite would probably not make money if they needed to pay for their wars themselves.

Some businesses benefit when a state goes to war, but not many. It is usually only the select businesses whose executives and shareholders belligerent governments are beholden to. But the question people who fear a corporation might go to war fail to ask is, who pays for modern war? Taxpayers gain nothing from war; they only lose. Businesses only profit when they get someone else (ie. taxpayers) to pay for it. If Halliburton had armed itself and gone into Iraq for oil, the costs would have far outweighed the benefits. It could have just traded with free people for it and saved millions on weapons. (See my take on the case of Iraq here.)

Some businesses benefit when a state goes to war, but not many. It is usually only the select businesses whose executives and shareholders belligerent governments are beholden to. But the question people who fear a corporation might go to war fail to ask is, who pays for modern war? Taxpayers gain nothing from war; they only lose. Businesses only profit when they get someone else (ie. taxpayers) to pay for it. If Halliburton had armed itself and gone into Iraq for oil, the costs would have far outweighed the benefits. It could have just traded with free people for it and saved millions on weapons. (See my take on the case of Iraq here.)

At the moment, some big corporations, usually oil companies, do attack people indirectly. They move into an area of people with no means to defend their land and the local government defends them against possible peasant unrest. It is possible to blame the corporations that bribe the state to use violence against these innocent people. However, if the state did not exist, the means of violence would not be paid for by the taxpayer. It would be paid for by customers, who would pay higher prices, and employees, whose wages would be lower. In effect, the tax would shift from individuals who do not benefit to those who do, and the prices might be exorbitant.

Moreover, bad PR costs a lot. People of conscience who find out that corporations are employing violence can boycott the corporations. All these things hurt sales. But we cannot force the people in the state who use violence to pay for it themselves, nor can we boycott the state. If a corporation stops caring about making money in the marketplace and only extracts it by force, it has become a state. Thus, the argument that if the state no longer existed, corporations would be just as able to commit violence does not follow. One way or another, anarchists oppose the initiation of force when done by anyone, be it a government, corporation, gang or otherwise.

But even with all this evidence corporations would not have unchecked and indominable power, it is still possible that corporations would commit overt violence, as if they were a government or a mafia, because they would probably still be disproportionately commanded by psychopaths, have lots of money and struggle for dominance. That is why the problem is not government per se, but the initiation of force. I do not care if it was a government or a corporation or just one person who killed 100 peaceful people; the problem is that they were killed. It could be hard to check corporations, like it is hard to check them and governments and other groups today. Not all information would reach everyone affected; not everyone would join in every boycott; not everyone would change due to public disgrace. So we need more ideas.

A stateless society would not be a completely peaceful utopia. How could it? When will we end aggressive behaviour? Few anarchists I know would even try. A lot of them believe that communities should separate from the state and become autonomous. Suffice to say, communities of free people would defend themselves against an aggressive corporation in the same way that they would defend themselves from any state or empire. That is something they have been doing for thousands of years. They or any anarchic society would need to have some kind of protection. That protection could come from the free market, as corporations competing for business would provide their customers with the protection they need. I understand the worry that those corporations could just turn on their customers and steal from them. However, businesses in a free market will provide enough customers with what they want that their owners will not want executives to start killing people. As Robert Murphy explains in detail, there is a market for security, and it could work very well against a corporation or any other organisation that wishes to harm people.

If a security company (or any other company that depends on repeat customers and good reputations, which is all successful ones not receiving state protection) kills or steals from or even enslaves a bunch of people, there are two problems. First, they will have less profit. I don’t think greed is necessarily bad: it depends how it is channeled. If you want to maximise profit, the rational solution might be to be a highly ethical corporation. In theory, and usually in practice, wherever free markets have existed (today’s markets are not very free), people are far wealthier, partly because they can pursue their self interest, partly because their motivation and creativity are higher, partly because they are forced to compete with others if they wish to remain profitable. If corporations want money, they are better off being good businesses and providing what the customers want, and if they do, the customers will come back.